|

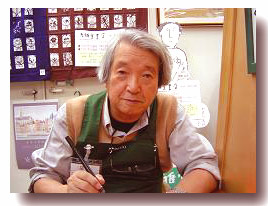

An Interview with Mitsumasa Anno

We're pleased to present our

interview with Mitsumasa Anno, the eminent

picture book creator whose book we

reviewed in our Autumn, 2003 issue.

【Mitsumasa

Anno】

Anno was born in Tsuwano of

Shimane Prefecture on March 20, 1926. He is

a graduate of the Yamaguchi Teacher Training College. Anno had dreamed

of becoming an artist from his earliest years. Eventually, he

began designing books after retiring from his job teaching at a primary

school. Urged on by Tadashi Matsui of Fukuinkan Shoten, he released his

first

picture book, "Topsy

Turvies" (Fukuinkan Shoten). Since that time, he

has been extremely active in the writing, illustration and designing of

picture books. With a firm grounding in both mathematics and

literature, Anno has published numerous books teeming with originality.

Some of his most famous picture books are "Anno's Magical ABC"

(Douwaya),

"Anno's Twice Told

Tales by the Brothers Grimm and Mr. Fox" (Iwanami

Shoten). His other writings include "E no Aru Jinsei"

(Iwanami Shoten)

and "Negai wa Futsu"

(Bunka Publishing Bureau)

Awarded countless international

honors including the prestigious Hans

Christian Andersen award, Mitsumasa Anno is fondly known around the

world as simply, "Anno". His unique and imaginative teaching-style had

captured the hearts and minds of his students while he was a

teacher in primary school. Anecdotes are still making the rounds of how

well he could tell funny stories, and about the countless episodes in

which his pupils were treated to a glimpse of his rich and warm

personality. Even within the short time we were privileged to spend

with him, we learned many things about his work with picture books.

|

|

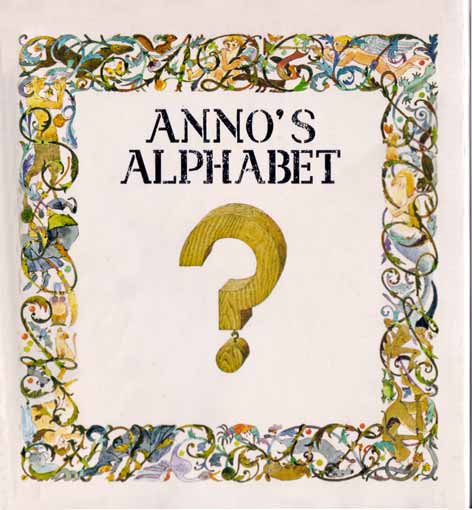

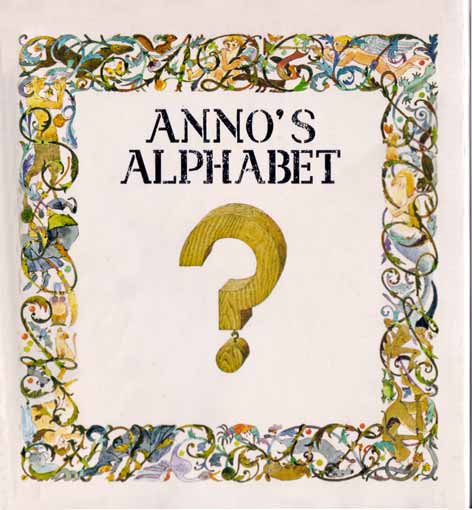

You're one of the few Japanese

authors who is truly active on an international level. Is it true that

the judges who honored you with the 1974 Kate Greenaway Award for

"Anno's Alphabet", didn't know

that you were a native of Japan?

Yes

it is. "ANNO" seems to be a surname that's used in other countries. My

understanding is that at that time, a book had to initially

be published in the U.K. prior to any other country for it to be

eligible

for the Kate Greenaway Medal. However, my editor (*1) was adamant about

the worthiness of this book and as an exception, it became a Commended

book and I received a prize certificate which is now on display at

the Mitsumasa Anno Museum.

(c) Mitsumasa Anno

|

|

"Anno's

Alphabet" is very

highly regarded and has received many awards from around the world, has

it not? Was it your original intention when you created this book that

it would be published abroad?

Well,

just because it's an alphabet book doesn't mean I'd originally

planned for international publication. But I do think that I wanted it

to be something that even people outside Japan would enjoy. For

example, if I'd used "Amedama", the romanized Japanese for "candy drop"

as my word for "A", that wouldn't have been possible. I asked the

teachers at the American school in Chofu city, Tokyo as well as various

American and British editors for advice in selecting appropriate words

for each letter. As an example, there was the time I wanted to choose

an original word for "H" and decided to use "Hag". So I drew a picture

of an old witch. My advisors said to me, "Hag" is generally used to

convey the image of an ugly old woman and it's relatively uncommon to

use it in reference to a witch. Even if you wanted to use this drawing

for "Witch", you'd have to remember that witches are not necessarily

old and ugly. Witches can be quite young and beautiful". So as you can

see, there was often a difference between my image of the word I'd

chosen and that of native speakers of English. I wound up having to

find an alternative word to use for many of the letters. I could

probably write a whole book on all the difficulties I came across in

just trying to complete this one picture book.

But thanks to all the trouble

we took in getting this book just right,

there was someone who recognized the worth of my book and said, "ABCs

have been in use throughout the ages since Roman times, but never have

they been expressed before in three-dimensional form". This review

made me happier than any other words of praise I received for this

book. In other words, the reader appreciated the fact that I had

succeeded in drawing the alphabet using trompe l'oeil or illusionism.

Having someone say "in a form never expressed

before" was an acknowledgement of my originality, so being praised in

this way moved me deeply.

|

|

"Anno's

Alphabet" wasn't

your first foreign publication, was it? I believe "Topsy Turvies"

was your first. How did this book come to be published abroad?

"Topsy Turvies" was first

published in Japan in 1968. Since it made the publisher's listings(*2),

it happened to catch the eye of editors in the U.S. and France. As a

result, it was released in those two countries in 1970. Although this

book had originally been published in Japan, it was only after the huge

foreign response that it became popular here as well. After my success

abroad, I began receiving regular inquiries on what I planned to write

next. I believe that having been published in the U.S. made the

greatest impact in that respect.

|

|

You've visited many countries

in your work, but have you ever felt uncomfortable when coming into

contact with foreign cultures?

Until I made my first trip

abroad, I'd been certain that there would be

huge differences in culture. But when I actually visited these

countries, I felt there was considerably more that we had in common

with these cultures than any differences. In the end, I even came to

feel that there were in fact no considerable differences at all. No

matter where in the world one is, there are some basic patterns we

follow. For example, most houses have a window from which it's possible

to see outside, and roofs are generally pointed so that the rain will

run off. Even with food, despite all the differences in taste that

there may be, no one anywhere will be feasting on something that we

couldn't possibly digest. From this perspective, although there are

differences in language and skin color, these differences in culture

aren't nearly as wide as one might believe.

But for my Journey books,

because I'm trying to depict the particulars

of life in each place, even the smallest details have to be absolutely

correct. Which reminds me, a certain Frenchman who had read my book

approached me and said, "I'm amazed that you're so familiar with France

even though you've never lived there. But there is one thing that you

haven't got quite right. You see, the people in France would never wash

their clothes in the river". I couldn't think of what to say. But

later, I remembered this painting

by van Gogh called The

Langlois

Bridge at Arles with Women Washing...(*3).

|

You often go abroad to sketch, but are you

one of those people who likes to plan everything out ahead?

Of course I rarely go on a trip

without checking up on my destination

in advance. But in most cases, once I'm there, I follow my nose. The

same goes for my drawings. If I see a scene I want to draw, I'll just

open my sketchbook, plop down on my bottom and go to it. I do

take

photos but rarely ever make use of them. Right

now, I'm working on the sixth volume of the Journey series. It's based

in Denmark. Hans Christian Andersen's 200th birthday comes up in 2005

so I'm writing this book to coincide with that event. It's due to be a

picture book where the reader travels through Andersen's fairy tales.

|

Next we'd like to

ask about

your involvement in the project where you collaborated with eight other

outstanding picture book

authors from around the world on the picture book, "All in

a Day". How were these eight other illustrators chosen? And what

made you

decide to create this book in the first place? Next we'd like to

ask about

your involvement in the project where you collaborated with eight other

outstanding picture book

authors from around the world on the picture book, "All in

a Day". How were these eight other illustrators chosen? And what

made you

decide to create this book in the first place?

(c) Mitsumasa Anno

This picture book came about

serendipitously while I was chatting with

Mr. Tanaka, who is with Dowaya, one of my publishers. It was decided on

right then and there. As for the eight illustrators involved, my

British and American publishers introduced some of them to me and some

of them were acquaintances. The inspiration for this book arose when I

was overwhelmed by the finest sunset on earth at Uskudar in Istanbul.

It

was such a fantastic and utterly gorgeous sunset to beat all sunsets.

But when I realized that the sun which was just setting in front on my

eyes was at the very same time, a rising sun in some other country, I

was totally thunderstruck. This meant that this same sun was going down

in a country at war and at that same time, it was rising in a country

at peace. This was an unbelievably shocking realization for me.

|

You illustrated two books, "The

Animals" and "The Magic Pocket",

in which Her Imperial Majesty Empress

Michiko, translated the poems of Michio Mado into English. We've heard

that Mr. Mado and your wife are cousins...

Their being cousins was simply

a coincidence, but since we're both in

the same field, we'd always hoped we would have a chance to work

together sometime. If you think about it, it's a strange

coincidence. It's very difficult to draw illustrations for poems. For

example, the elephant poem goes, "Little elephant, little elephant what

a long nose you have". You can't just draw a picture of an elephant

with a long nose for a poem like that. I think descriptive

illustrations for a poem would really show a lack of taste.

|

|

Are you particularly conscious of your

audience, in other words children, when you're creating a picture book?

I don't really make a

distinction between the books I write for

children and those for adults. I don't draw to please children, I draw

to please myself. Taking off on a tangent here, for me, drawing is my

work. I was once asked at a symposium, "Why do you draw?" I knew what

they would have liked for an answer, "I draw for the children of Japan

who represent our future, blah, blah, blah". But what I actually wound

up saying was, "I draw because that's my work. I made it my work

because it's what I like to do". Michael Ende then said, "The same goes

for me. I'm just like Anno-san", while Tasha Tudor said, "I do my

work so that I can buy

lots of flower bulbs".

|

|

There are still many wonderful

picture books and children's stories in Japan which have never been

made available abroad. Do you have any advice for Japanese writers and

publishers who hope to see their work published overseas?

I think we're extremely

fortunate here in terms of access to foreign books. Thanks to our

publishers, literature from all around the world gets translated into

Japanese. The drawback is, because of the rapid movement

towards westernization after the Meiji era, we've developed an

inferiority complex about our own culture. Consequently, we have a

tendency to believe foreign books are better than ours. But in

reality, Japanese literature is just as good, if not better than that

of any other country. In fact, I believe there's some wonderful

literature in Japan that would easily top any world standard. As

long

as it's decently translated, there's no reason why Japanese literature

should be considered inferior to any. I really hope to see more

Japanese books

translated into foreign languages.

|

|

We know that you've published

many books in addition to your picture books. Would you be kind enough

to tell us about some of your recent releases?

In

December 2003, my book, " Seishun no

Bungotai" [Bungotai(Japanese

literary style) for the Young] was published. Literary works written in

the literary style of the Meiji and Taisho eras have a keenness and

high-mindedness which should appeal to people today. I wrote

this book with the hope that it would remind everyone that we shouldn't

forget the bungotai writing style. In my book, I've recommended

Ohgai Mori's translation of " Sokkyo

Shijin" [An Improvised Poet] by Hans Christian Andersen, Ichiyou

Higuchi's Takekurabe

[Marking our

(c) Mitsumasa Anno Heights], Touson Shimazaki's " Hatsukoi" [First

Love]. I hope you'll take this opportunity to read some books written

in bungotai. |

This isn't directly related to

your work with picture books, but we've heard that just around the time

you first started out as an artist, there was a project which gave you

some grief. Would you tell us a little about your experience and how it

affected your work thereafter?

This was a project involving a book design where I had to think up

several different patterns or ideas. I somehow came up with fifteen

different versions but then, the editor said, "I'd like one more

version". You wouldn't believe how much trouble I had trying to think

up this 16th idea. From the editor's standpoint, I suppose it was just

"one more", but remember, this was after I'd already wracked my brains

for fifteen, so you can imagine how difficult it was. A mathematician

can tell you how challenging it is to come up with just two different

solutions for one math problem. Just when I was really at the end of my

wits from not being able to think up anything, I looked up. Around me I

saw the faces of the people in the train I was on, and suddenly I

realized something. You see, people's faces are made up of some very

basic components, two eyes, a nose and a mouth. But in spite of that,

everyone has a different face. There are millions of different

variations of the human face, as many faces as there are people. And I

finally realized there should be an almost infinite number of possible

ideas for a book design. This was a big turning point for me. It may

sound like I'm exaggerating, but I felt as if I'd been provided with a

revelation. But this is something you really have to find out for

yourself. It would be meaningless for someone to come up to you and

simply tell you, "Look at all the people's faces. Since there are an

infinite variety of faces, by the same token, you should be able to

think up as many as

different variations on a theme as you need." A message has to

hit hard - enough to make you wince - for it to really get through.

Since that time though, I've never had any trouble trying to design a

book.

Mr. Anno, thank you so very

much for this wonderful interview.

|

|

We'd also like to express our

thanks to the chief editor at Fukuinkan Shoten, Minoru Tamura, Manager

of the Editorial department at Chikuma Shobo, Tetsuo Matsuda and

Michiko Nakagawa of the first editorial office for their kind help in

making this interview possible.

(May Takahashi)

|

(*1) The famous expert on

Beatrix Potter, Judy Taylor.

(*2) Fukinkan Shoten Publishers regularly distributes listings of its

publications to foreign publishers.

(*3) You can see an image of this famous painting here: http://www.vangoghgallery.com/painting/p_0397.htm

|

A list

of some of Mitsumasa Anno's

most famous books and

distinctions

Fushigi na

E (Mysterious

Pictures), Fukuinkan Shoten, 1968

Jeux de consruction, France,

1970

Topsy Turvies, USA, 1970

Zwergenspuk, Switzerland, 1972

Den Tossede Bog, Denmark, 1974

Topsy Turvies, USA, 1989

(reprinted)

Chyi Miaw Gwo, Taiwan, 1990

1970

Chicago Tribune Honor Award

ABC no Hon

- hesomagari no

arufabetto

(Book of ABCs - a twisted alphabet), Fukuinkan Shoten, 1974

Anno's Alphabet, UK, 1974

Anno's Alphabet, USA, 1975

1974 The

Minister of Education's Art

Encouragement Prize for New Artists

1974 Kate

Greenaway Commended

1975

Brooklyn Museum of Art Award

1975 Boston Globe Horn Book

Award

(Picture Books)

Tabi no

Ehon, (Journey book)

Fukuinkan Shoten, 1977

En rejse, Denmark, 1978

Ce jour-la', France, 1978

De reis van Anno, Netherlands,

1978

Wo ist der Reiter?,

Switzerland, 1978

Anno's Journey, UK, 1978

Anno's Journey, USA, 1978

II viaggio incantat, Italy,

1979

El Viaje de Anno, Spain, 1979

En Resa, Sweden, 1979

Leu Jy Huey Been, Taiwan, 2003

Tabi no

Ehon II, (Journey book

II) Fukuinkan Shoten, 1978

Italien rejsen-Enordlos

billedbog, Denmark, 1979

Le jour suivant..., France,

1979

Anno resist verder,

Netherlands, 1979

Anno's Italy, UK, 1979

Anno's Italy, USA, 1979

El viaje de Anno(II), Spain,

1981

Leu Jy Huey Been II, Taiwan,

2003

1979 BIB

Golden Apple Award

1980

Graphic Award, Bologna

Children's Book Fair

Tabi no

Ehon III, (Journey book

III) Fukuinkan Shoten, 1981

Englandsrejsen, Denmark, 1982

Se'jour en Grande-Bretagne,

France, 1982

Anno resist door Engelad,

Netherlands, 1982

El Viaje de Anno(III), Spain,

1982

Anno's Britain, UK, 1982

Anno's Britain, USA, 1982

Leu Jy Huey Been III, Taiwan,

2003

Tabi no

Ehon IV, (Journey book

IV) Fukuinkan Shoten, 1982

USA-rejsen, Denmark, 1983

USA, France, 1983

Anno Reist door Amerika,

Netherlands, 1983

El Viaje de Anno(IV), Spain,

1983

Anno's USA, UK, 1983

Anno's USA, USA, 1983

Leu Jy Huey Been IV,

Taiwan, 2003

1984 Hans

Christian Andersen Award

for Illustration

Maarui

Chikyu no Maru ichi nichi

(Around the clock in a round world), Dowaya, 1986

All in a Day, UK, 1986

All in a Day, USA, 1986

Shyh Tieh Dih I Tian, Taiwan,

1992

The

Animals, Suemori Books, 1992

The Animals, USA, 1992

The Magic

Pocket, Suemori

Books, 1998

The Magic Pocket, USA, 1998

Tabi no

Ehon V, (Journey book V)

Fukuinkan Shoten, 2003

Anno's Spain, USA, 2004

Sur les traces de Don

Quichotte, France, 2004

Seishun no

Bungotai (Bungotai

for Youths), Chikuma Shobo, 2003

|

Japanese Children's

Books

Japanese Children's

Books

Contents

Contents

Highlight: Interview

with Anno Mitsumasa

Highlight: Interview

with Anno Mitsumasa Japanese

Picture Books

Japanese

Picture Books Seasonal Picture Books

Seasonal Picture Books Japanese Picture Books in English

Japanese Picture Books in English In Celebration of the New Year: Osechi Ryori

In Celebration of the New Year: Osechi Ryori

Yes

it is. "ANNO" seems to be a surname that's used in other countries. My

understanding is that at that time, a book had to initially

be published in the U.K. prior to any other country for it to be

eligible

for the Kate Greenaway Medal. However, my editor (*1) was adamant about

the worthiness of this book and as an exception, it became a Commended

book and I received a prize certificate which is now on display at

the Mitsumasa Anno Museum.

Yes

it is. "ANNO" seems to be a surname that's used in other countries. My

understanding is that at that time, a book had to initially

be published in the U.K. prior to any other country for it to be

eligible

for the Kate Greenaway Medal. However, my editor (*1) was adamant about

the worthiness of this book and as an exception, it became a Commended

book and I received a prize certificate which is now on display at

the Mitsumasa Anno Museum. Well,

just because it's an alphabet book doesn't mean I'd originally

planned for international publication. But I do think that I wanted it

to be something that even people outside Japan would enjoy. For

example, if I'd used "Amedama", the romanized Japanese for "candy drop"

as my word for "A", that wouldn't have been possible. I asked the

teachers at the American school in Chofu city, Tokyo as well as various

American and British editors for advice in selecting appropriate words

for each letter. As an example, there was the time I wanted to choose

an original word for "H" and decided to use "Hag". So I drew a picture

of an old witch. My advisors said to me, "Hag" is generally used to

convey the image of an ugly old woman and it's relatively uncommon to

use it in reference to a witch. Even if you wanted to use this drawing

for "Witch", you'd have to remember that witches are not necessarily

old and ugly. Witches can be quite young and beautiful". So as you can

see, there was often a difference between my image of the word I'd

chosen and that of native speakers of English. I wound up having to

find an alternative word to use for many of the letters. I could

probably write a whole book on all the difficulties I came across in

just trying to complete this one picture book.

Well,

just because it's an alphabet book doesn't mean I'd originally

planned for international publication. But I do think that I wanted it

to be something that even people outside Japan would enjoy. For

example, if I'd used "Amedama", the romanized Japanese for "candy drop"

as my word for "A", that wouldn't have been possible. I asked the

teachers at the American school in Chofu city, Tokyo as well as various

American and British editors for advice in selecting appropriate words

for each letter. As an example, there was the time I wanted to choose

an original word for "H" and decided to use "Hag". So I drew a picture

of an old witch. My advisors said to me, "Hag" is generally used to

convey the image of an ugly old woman and it's relatively uncommon to

use it in reference to a witch. Even if you wanted to use this drawing

for "Witch", you'd have to remember that witches are not necessarily

old and ugly. Witches can be quite young and beautiful". So as you can

see, there was often a difference between my image of the word I'd

chosen and that of native speakers of English. I wound up having to

find an alternative word to use for many of the letters. I could

probably write a whole book on all the difficulties I came across in

just trying to complete this one picture book. Next we'd like to

ask about

your involvement in the project where you collaborated with eight other

outstanding picture book

authors from around the world on the picture book, "

Next we'd like to

ask about

your involvement in the project where you collaborated with eight other

outstanding picture book

authors from around the world on the picture book, " In

December 2003, my book, "

In

December 2003, my book, "